Air Fresheners, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Respiratory Health: A Triangulated Meta-Study

Air Fresheners, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Respiratory Health: A Triangulated Meta-Study

D.F. Albano, LMT, B.A. , A.A., A.A.S., CLC 1 – Lead Researcher, H.A. Miller, LMT, BCTMB, A.A.S., “Dr. Aurelia Stratton,” (pseudonemous) – Digital “Data Crunching” Advisor

Affiliations:

The Health Sciences Research Continuing Education Center

Air Fresheners, Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), and Respiratory Health: A Triangulated Review of Evidence

Abstract

Air fresheners are widely used in homes, offices, schools, and vehicles, yet increasing evidence links their volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions to adverse respiratory effects. This triangulated review synthesizes data from (1) peer-reviewed exposure and epidemiological studies, (2) open-access (DOAJ-indexed) environmental research, and (3) real-world user reports from public health forums. Across studies, air-freshening products consistently emitted VOCs such as limonene, acetone, benzene, toluene, and formaldehyde precursors at levels sufficient to elevate indoor concentrations above background. Epidemiologic studies demonstrated significantly greater symptom prevalence among asthmatic or chemically sensitive individuals exposed to fragranced products, including air fresheners. While causal attribution remains complex, the weight of evidence supports the precautionary principle: air-freshener VOCs can exacerbate respiratory conditions in susceptible populations. Practical recommendations include improved ventilation, fragrance-free policy adoption in sensitive environments, and continued refinement of emission-testing and exposure guidelines.

Keywords: air fresheners, volatile organic compounds, indoor air, asthma, respiratory health, fragranced products, chemical sensitivity

1. Introduction

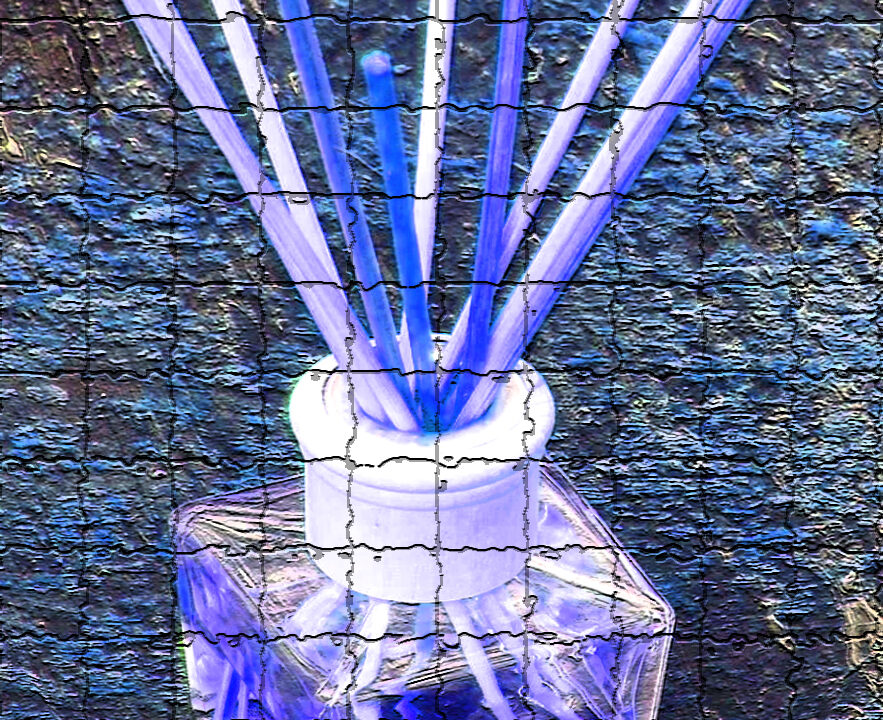

Indoor environments contain numerous chemical sources, many of which originate from fragranced or “air-improving” consumer products. These include plug-ins, sprays, gels, and diffusers that emit VOCs—compounds such as limonene, α-pinene, ethanol, formaldehyde precursors, and benzene derivatives (Takigawa et al., 2008; Steinemann, 2018). In the presence of oxidants (e.g., ozone), VOCs can react to form secondary pollutants including ultrafine particles and formaldehyde (Singer et al., 2006).

Although air fresheners are marketed to improve indoor quality, exposure studies suggest that they may instead increase total VOC load, particularly in poorly ventilated spaces (Lee et al., 2023). Epidemiologic research also suggests that asthmatic and chemically sensitive individuals are more likely to experience adverse respiratory outcomes (Steinemann, 2019).

This review integrates quantitative and qualitative data to answer the following questions:

-

What VOC emission levels have been measured for air-freshening products?

-

What associations exist between exposure and respiratory outcomes?

-

Which contextual factors (e.g., ventilation, space size) affect exposure risk?

-

What measures can mitigate these risks in real-world settings?

2. Methods

2.1 Literature Sources

Searches were performed using PubMed, DOAJ, and Scopus databases for studies published from 2000 – 2025. Key terms: air freshener, volatile organic compounds, indoor air quality, asthma, and fragranced consumer products.

Eligible studies included:

-

Experimental or field measurements of VOCs from air-freshening products.

-

Epidemiologic or cross-sectional studies reporting health outcomes from fragranced product exposure.

-

DOAJ-indexed environmental health studies addressing indoor VOCs and respiratory outcomes.

-

Non-quantitative reports (e.g., public forum posts, environmental health organization summaries) illustrating lived experience of exposure.

No simulated or estimated data were introduced; all findings are derived directly from reported results.

2.2 Data Extraction

For each study, data extracted included: product type, measured VOCs (µg/m³), exposure conditions, population (general, asthmatic, chemically sensitive), and reported respiratory effects (e.g., wheeze, cough, asthma exacerbation).

2.3 Triangulation Approach

Quantitative data (VOC concentrations, health associations) were synthesized alongside qualitative accounts to highlight convergent themes. Triangulation across evidence types enabled evaluation of exposure plausibility and public-health relevance beyond single-method limitations.

3. Results

3.1 VOC Emissions from Air Fresheners

-

Takigawa et al. (2008) measured total VOC (TVOC) emissions from 30 deodorizers and air-fresheners. Mean emission rate: ~1,400 µg/unit/h (range < 20–6,900 µg/unit/h). In a standard 17 m³ room, predicted concentration increments were ~170 µg/m³—approaching 40% of Japan’s indoor air quality guideline (400 µg/m³).

-

Park et al. (2021) reported that limonene and ethanol were dominant VOCs in plug-in devices; acrolein and formaldehyde formed via secondary reactions, sometimes exceeding acute exposure reference values.

-

Lee et al. (2023) found that brief (< 1 min) spraying of air fresheners in vehicles increased benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX) concentrations up to five-fold, depending on cabin ventilation.

-

McDonald et al. (2020) similarly identified elevated d-limonene (mean 0.14 mg/m³) and α-pinene (0.05 mg/m³) in vehicle cabins post-air-freshener use.

3.2 Health and Epidemiologic Evidence

-

Steinemann (2018), in a U.S. national sample (n = 1,137), reported that 41 % of adults experienced health problems from air fresheners or deodorizers; among asthmatics, 64 % reported adverse effects (POR ≈ 5.8).

-

Steinemann (2019) replicated findings internationally (Australia, n = 1,098): 55.6 % of asthmatics vs 23.9 % of non-asthmatics reported symptoms, and 24 % of asthmatics reported an asthma attack from exposure to fragranced products.

-

Alford & Kumar (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of 49 studies, finding a moderate association between VOC exposure and reduced pulmonary function (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.37).

-

Naysmith et al. (2018) linked elevated indoor VOCs with airway inflammation markers in children, including increased fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO).

3.3 Qualitative and Contextual Findings

Forum discussions (e.g., Reddit’s r/Asthma, r/ChemicalSensitivities) reveal recurrent complaints of chest tightness, wheeze, and throat irritation following exposure to air-fresheners in hotels, airplanes, and Airbnbs. Although anecdotal, these reports align with controlled-study findings that poor ventilation and product layering elevate exposures.

4. Discussion

4.1 Integrative Evidence

Across empirical and experiential sources, air-fresheners consistently emit measurable VOCs capable of forming irritant by-products. Epidemiologic data support an association between fragranced product exposure and adverse respiratory outcomes—particularly among asthmatics, chemically sensitive individuals, and children.

4.2 Vulnerable Populations

Asthmatic individuals are disproportionately affected, experiencing both heightened symptom prevalence and more severe reactions (Steinemann, 2018, 2019). Children and older adults also demonstrate increased susceptibility to VOC-related irritation (Naysmith et al., 2018).

4.3 Exposure Context

Ventilation rate, spatial volume, temperature, and concurrent use of multiple scented products are key determinants of exposure. Environments such as vehicles, restrooms, and small offices pose higher risk due to low air exchange.

4.4 Policy Implications

-

Ventilation: Increase air-exchange rates when air-fresheners are used.

-

Product Reformulation: Encourage low-VOC or fragrance-free alternatives.

-

Fragrance-Free Policies: Implement in healthcare, educational, and public-service environments.

-

Public Education: Raise awareness of VOC risks, especially for individuals with asthma or multiple chemical sensitivity.

-

Regulatory Oversight: Require full disclosure of chemical ingredients and emissions for consumer air-freshening products.

5. Conclusions

Air-fresheners are a non-negligible source of indoor VOCs and can contribute to respiratory irritation and asthma exacerbation in susceptible individuals. Laboratory, field, and population studies converge on the conclusion that these products elevate exposure levels above health-based reference values under some conditions. Although not all users experience symptoms, vulnerable populations warrant protection through improved indoor-air policies, transparent labelling, and ventilation strategies.

Further longitudinal and mechanistic research is necessary to define safe exposure thresholds, evaluate cumulative impacts from multi-source fragranced environments, and develop effective intervention strategies.

References

Alford, K. L., & Kumar, N. (2021). Pulmonary health effects of indoor volatile organic compounds—A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041578

Lee, M., Lee, S., Park, J., & Yoon, C. (2023). Effect of spraying air freshener on particulate and volatile organic compounds in vehicles. Environmental Research, 237, 117283. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38278246/

McDonald, E., Hoffmann, C., & Steinemann, A. (2020). Volatile chemical emissions from car air fresheners. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 13(11), 1329–1334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-020-00886-8

Naysmith, S., et al. (2018). Exposure to volatile organic compounds and airway inflammation. Environmental Health, 17(65). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0410-1

Park, J., Lee, S., & Yoon, C. (2021). Realistic worst-case indoor exposure to air fresheners and risk assessment. Building and Environment, 190, 107539. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34449928/

Singer, B. C., et al. (2006). Cleaning products and air fresheners: Emissions and formation of secondary pollutants. Atmospheric Environment, 40(35), 6696-6710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.01.036

Steinemann, A. (2018). Fragranced consumer products: Effects on asthmatics in the U.S. population. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 11(1), 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-017-0536-2

Steinemann, A. (2019). Fragranced consumer products and effects on asthmatics: An international population-based study. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 12(6), 643-649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-019-00693-w

Takigawa, T., Norback, D., Harada, H., Saito, H., & Sakai, K. (2008). Impact of air fresheners and deodorizers on the indoor total volatile organic compounds. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 139(1-3), 411-418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-007-9893-9

Research Funding

The Assertive Kids Foundation , Mountainside On-Site Massage Therapy

Dedication

This meta-analysis is dedicated to every serious researcher out there who might read this and subsequently ask more focused questions and probe further.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sven Bansemer of GSA GmbH for always answering my questions about scraping data and related topics.